Read any book or article about General Motors during the early ‘60s and it inevitably mentions the corporation’s infamous racing ban of 1963. It’s generally accepted that the action was a simple solution to GM’s fearfulness of being broken up over antitrust concerns. There really hasn’t been conclusive evidence to completely support that, however.

Yes, GM was investigated for antitrust violations during the early ‘60s. Examples included sales dominance of diesel electric locomotives by its Electro-Motive Division, DuPont’s ownership of 63 million shares of GM stock (who also happen to be GM’s largest paint and fabric supplier), perceived dealership favoritism toward GM Acceptance Corporation (GMAC) over local banks for new car financing, and discrimination against “discount dealers” in Southern California. And then there was Robert F. Kennedy.

Ray Nichels (left), Bunkie Knudsen (left center), Harley Earl (center), and driver Cotton Owens (right center) celebrate Pontiac’s first-ever NASCAR win at Daytona Beach in February 1957. It would set the stage for a series of great success that would garner Pontiac the image as GM’s performance division.

There’s no doubt that when you’re the world’s largest corporation, the competition has its sights set on you. Despite all the negative publicity generated by said antitrust examples, General Motors still sold more vehicles than all other automakers combined during the early ‘60s! I haven’t ever been totally convinced that its abrupt decision against racing in February 1963 was solely due to antitrust. After all, when you’re selling that many new vehicles, would the loss of the limited-number of off-road race engines really be felt?

With the recent discovery of documents and newspaper reports from that time a different story comes to light. It seems these matters likely played an equal or greater part in GM’s decision to enforce adherence to the AMA’s Resolution of 1957. Here’s a fresh look that seems to have been lost to history, until now.

Robert Kennedy’s Antitrust Action in 1961

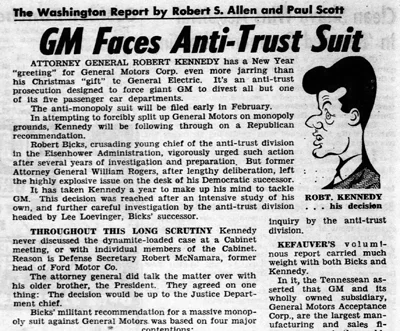

General Motors, with its five passenger car divisions was an industry giant just like General Electric, General Mills, U.S. Steel, and AT&T were in their respective industries. In January 1961, immediately after John Kennedy’s Presidential inauguration and the appointment of his brother, Robert Kennedy as Attorney General, the Kennedy Administration vowed action on a campaign pledge that big businesses were too big. Robert Kennedy announced investigations and prosecution of the country’s largest corporations should it be found that any violated antitrust laws. The Eisenhower administration had initiated an investigation against General Motors and when Robert Kennedy took over, his sights were set on GM.

Attorney General Robert Kennedy announced in late-December 1961 that he would file suit against General Motors for antitrust violations.

In late-December 1961, on the heels of antitrust suit announcements against other industry giants, Robert Kennedy planned to take action against General Motors to dissolve its perceived monopolistic hold on the new car marketplace and force it to divest in all but one of its vehicle divisions. The two-year long investigation that began with the previous administration included numerous complaints against GM from its competitors. The antitrust suit against GM was never officially filed, however, and by August 1962 Kennedy was being criticized for its delay. It’s possible that, like Kennedy’s potential suit against General Electric, it was negotiated and settled behind closed doors. It’s also possible that Kennedy and his Assistant Attorney General Lee Loevinger realized that its case against GM wasn’t as solid as originally assumed.

By August 1961 Kennedy was being criticized for the delay in filing an antitrust lawsuit against General Motors.

Motorsports Backstory

Now let’s step back several years to understand the other side of the story. Motorsports always had a strong following since the inception of the automobile and the popularity of speed-based contests exploded during the ‘50s. The county was just getting back to normal after World War II, the economy was bustling, the interstate system was being developed, and NASCAR had just been founded. New vehicle sales were on the rise and manufacturers recognized how successes in various motorsport venues directly correlated to new vehicle sales. It ultimately led to the “Win on Sunday, sell on Monday” mantra because victories translated into bankable dollars.

The positive impact that racing wins had on manufacturers’ profitability made internally-funded race programs justifiable. Each brand fought hard for a horsepower edge on the NASCAR tracks and straight-line acceleration contests, and that created a fierce competition within the industry. Manufacturers hired the best talent for research and development and to prepare their vehicles for the next race, and they paid to put the best drivers behind the wheel each week. Add to that sponsorship monies so their hottest street cars could pace the top billed events.

The crash at 24 Hours of LeMans that claimed several dozen lives on June 11, 1955 was front page news.

If you weren’t into racing or didn’t read the sports section of your local newspaper to see how the various brands stacked, speed contests probably didn’t matter much to the average consumer. Motorsports was propelled into mainstream media on May 30, 1955, however, when a violent crash at the Indianapolis 500 claimed the life of racer Bill Vukovich. Then approximately 80 persons—mostly spectators—lost their lives less than two weeks later on June 11 at the 24 Hour of LeMans endurance race. While the general public cringed at these tragedies, neither incident did much to curb the manufacturers’ racing efforts—at least at first. It wasn’t until industry-wide fears of federal government prodding to slow the developmental pace that collective action was taken.

Pontiac Hires Lou Moore

Pontiac’s Chief Engineer, George Delaney announced on December 13, 1955 that the division had hired Lou Moore—a veteran engineer that had amazingly racked up five Indy 500 wins—to lead a special engineering project centered in Indianapolis. Moore’s objective was to continuously improve Pontiac’s competitiveness in stock car racing. Moore recruited Cotton Owens to drive the Moore-prepped ’56 Pontiac at the Grand National race on Daytona Beach on February 26, 1956, but the Pontiac finished closer to the bottom than the top. The Moore-prepped Pontiac effort improved over the next few races, but Lou Moore passed away unexpectedly on March 25, 1956. Pontiac was unable to claim a checkered flag that season.

The December 17, 1955 issue of The Star Press wrote of Pontiac hiring Lou Moore to lead motorsports development projects.

Bunkie Knudsen was an industry leader who helped turn GM’s ailing Pontiac division into a seemingly overnight success on the notion that “You can sell an old man a young man’s car.” He was made Pontiac’s General Manager in July 1956 and immediately set out to further transform Pontiac’s conservative reputation with the buying public. He brought in the best forward-thinking engineering talent he could find. He stole Pete Estes away from Oldsmobile and positioned him as Pontiac’s Chief Engineer and he hired John DeLorean away from Packard and placed him over advanced engineering. The direction of Pontiac’s new leadership team clicked well with its forward-thinking veteran engineers such as Mac McKellar, who was instrumental in the development of the Pontiac V8 platform for ‘55 as well as the “extra horsepower” 285 hp package introduced in ’56 to make the 316.6 ci V8 competitive in motorsports.

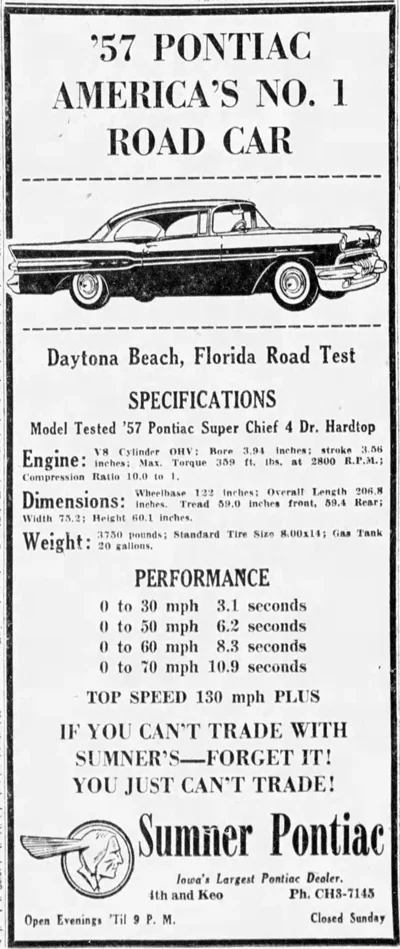

The groundwork had been laid, new leadership was in place, and Pontiac’s complete transformation was underway. The original 287-ci V8, which grew to 316.6 for ’56, was up to 347 ci for ’57 and Tri-Power induction debuted. The ’57 Pontiac exterior was stripped of its aged “silver streak persona.” Knudsen could feel that Pontiac was on the verge of racing success and he believed that Pontiac needed someone as qualified as Lou Moore to direct its racing operation. Ray Nichels was brought in during September 1956 for that task.

On December 17, 1956 The Indianapolis News shared the details of Ray Nichels hiring by Pontiac.

Pontiac’s First Stock Car Win

Pontiac entered two Nichels-prepped ’57 Pontiacs in NASCAR’s Grand National race at Daytona Beach on February 17, 1957. Banjo Matthews qualified for the pole position in one and Cotton Owens started in third with the other. Knudsen was so confident in his division’s success during the 1957 Speed Week events that he personally made the trip to Daytona Beach to take part in the activities. The Nichels-prepped Pontiacs didn’t disappoint. Owens provided Pontiac with its first ever NASCAR win and set an average speed record of 101.6 mph in the process! Knudsen and Nichels stood next to GM’s Harley Earl as he presented Owens with the GM-sponsored trophy that day. With its showing on the beachfront, Pontiac catapulted itself as the brand to beat.

The February 18, 1957 printing of The Orlando Sentinel reported Pontiac’s first ever NASCAR win.

Horsepower amongst all manufacturers was growing at an alarming rate during the late ‘50s. Not only were auto enthusiast magazines covering on-track rivalries, manufacturers’ advertisements promoted what sold—performance! The 1955 tragedies were a stark reminder of the general dangerousness that racers and spectators were exposed to at speed events, yet the meteoric rise of motorsports popularity with consumers who may attempt to emulate that on public roads was a growing concern. GM’s president at the time, Harlow Curtice, recommended to the AMA in February 1957 that automakers deemphasize performance as a subtle attempt at avoiding government regulations that could result in federally-imposed performance limits.

Pontiac advertisements like this were commonplace in February 1957 after its remarkable wins at Daytona Beach.

What is the AMA?

If you’re interested in automotive history even in the slightest, you’re likely familiar with the AMA, but what exactly is it? The Automobile Manufacturers Association (or AMA) was the outgrowth of the Association of Licensed Automobile Manufacturers (ALAM). ALAM was formed in the early 1900s as a national group to pool the interests and ideology to perfect automobile development, discuss and formulate collective positioning on industry issues, and protect against patent infringement. Expected membership was every major automaker in the country at that time. ALAM and the many other similar-but-smaller trade groups ultimately melded into Automobile Manufacturer’s Association (AMA).

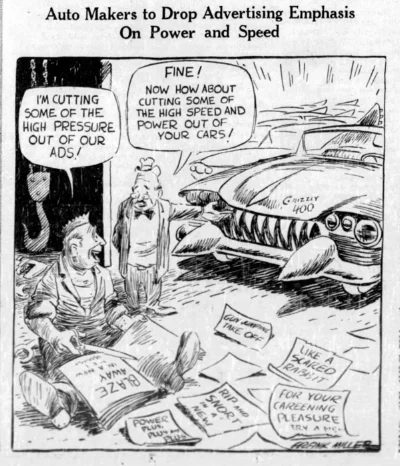

Every manufacturer was touting their hottest vehicle’s acceleration capabilities during 1957. While it generated sales, it also caused concerns of governmental interference.

Due to a patent infringement squabble with a founding member of ALAM, Henry Ford refused to join any manufacturer association throughout his tenure as Ford Motor Company’s president. His disdain toward such groups applied to AMA, likely because of its loose relationship to ALAM. Ford’s grandson, Henry Ford II, who took over the leadership role at Ford Motor Company decided to join the AMA in 1956. And George Romney, who was AMC’s top man, was AMA president.

Even the satirical cartoonists of the day were poking fun at the auto industry’s obvious emphasis on performance.

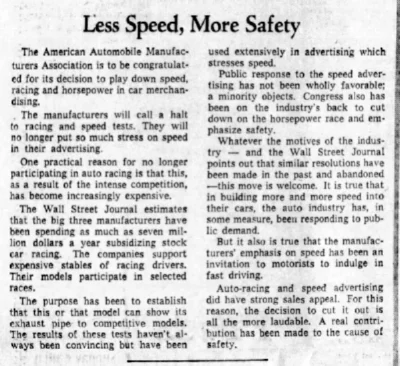

AMA “Resolution” of June 1957

Following Curtice’s suggestion as well as considering the arguments from independent racers who wanted manufacturers out of racing because their unlimited budget and developmental resources gave them an unfair advantage and allowed them to “buy” wins, the AMA adopted a “Resolution” at its June 6, 1957 meeting. In simplest terms, the Resolution of 1957 was an agreement by all manufacturing company members to independently de-emphasize performance in their respective advertisements and publicity materials and instead draw attention toward “useful power” at highway speeds and safety features and equipment. It worked, at least for a while.

Articles such as this, which ran in the June 8, 1957 printing of The Des Moines Register announced to the county that automakers were pulling out of racing and will focus efforts on safety.

Some members ultimately interpreted the resolution as an agreement to simply refrain from openly sponsoring or endorsing corporate racing activity. The “private” racer could, however, continue his competitive efforts unabated. In the months that followed manufacturers developed backdoor programs to quietly provide factory goodies to the best “amateur” racers, which ensured their brand’s success in motorsports.

On June 6, 1957, the AMA adopted a resolution that all member companies would refrain from engaging in motorsport activities. The article in the June 5, 1957 issue of The Akron Beacon contains a different perspective.

Ford Motor Company Buys Autolite

In April 1961, Ford Motor Company purchased Autolite for $28 million and that included taking possession of the spark plug manufacturer’s $2 million racing endorsement program. Henry Ford II reasoned that because Autolite wasn’t an auto manufacturer but instead a supplier, and since that program (and its related contracts) was established prior to the acquisition, Autolite’s program wasn’t subject to the terms of the AMA agreement. Ironically, Henry Ford II was elected as AMA president and began his one-year term on June 15, 1961. With it came much publicity that the man whose company had just purchased a $2 million racing program was now at the helm of the organization that created an agreement opposing racing in June 1957.

The Philadelphia Inquirer reported on May 29, 1961 that the Ford Motor Company had purchased Autolite Spark Pulgs and with it came a $2-million dollar racing contract.

Roy Abernethy’s Role at AMC

In November 1961 Roy Abernethy, AMC’s executive vice-president of marketing temporarily took over as that company’s general manager when George Romney took a political leave of absence. Then in February 1962, Romney officially resigned from his position as president and CEO of AMC after announcing his candidacy in Michigan’s gubernatorial race days earlier. Romney remained on AMC’s board of directors, however, and saw that Abernethy permanently succeeded him as AMC’s general manager. Romney went on to win the November 1962 election and resigned from AMC entirely. Abernethy was named AMC’s CEO on November 15, 1962.

Ford Withdraws from AMA Resolution

By the summer of 1962, the Super Duty 421 Pontiacs and 409-ci Chevrolets were cleaning house in all forms of racing. Even though those divisions weren’t actively sponsoring their own race teams, development of the race components that professional and amateur racers competed with each weekend intensified. And Henry Ford II took notice.

On June 12, 1962, The Detroit Free Press reported that Henry Ford II had withdrew his company from the AMA agreement.

Wanting to further Ford Motor Company’s race program because of its impact on profitability, Henry Ford II announced in June 1962 that his company officially withdrew from the AMA’s Resolution of 1957, reasoning that few manufacturers truly abided by it. That action led to an uproar within the industry. Chrysler immediately followed suit citing that Ford’s abandonment nullified of the original agreement. General Motors officially responded in press release form on June 11, 1962 stating that it would continue endorsing the program while it evaluated others’ moves. Congress, on the other hand, vowed to investigate why automakers had abandoned the resolution.

Putting Pressure on GM

In the months that followed Ford’s and Chrysler’s withdraw from the AMA agreement, Roy Abernethy essentially defended his corporation’s decision to abide by the agreement and openly criticized others who continued developing race components Newspaper articles at the time all but suggested that Abernethy was rather spiteful that his competitors’ racing success was taking sales away from AMC, who was having its own banner year in 1963 and also happen to launch its own performance vehicle—the Rambler.

AMC’s Roy Abernethy openly criticized his competitors’ involvement in racing activity at a January 18, 1963 engagement at which he spoke.

On January 18, 1963, Abernethy spoke before Detroit’s Adcraft Club, an organization comprised of marketing and advertising companies in that city. In his speech, Abernethy was critical of the automakers that recently withdrew from the AMA agreement and that their recent advertisements promoting speed and horsepower would draw unwanted attention from the federal government and negative public sentiment.

GM’s Official Ban on Racing

In the hours that followed Roy Abernethy’s speech, General Motors’ top executives called a meeting to re-evaluate its position on racing involvement. It’s unclear if GM was actually pressured by the federal government to slow down its performance vehicles or it was simply fearful of that occurrence, it ultimately decided that its divisions were to immediately cease all race programs and discontinue availability of such engines as Pontiac’s Super Duty 421 and Chevrolet’s 427-ci “mystery motor.”

This internal memo distributed within Pontiac on January 24, 1963.

The directive was handed down to the divisions. We can only assume an internal memo was distributed but any such example has yet to surface. On January 24, 1963, however, Pontiac issued its own internal bulletin that announced the immediate discontinuance of its Super Duty 389 and 421 engines. The stage had already been set for race at Daytona Beach a few weeks later and vehicles and components were already in the public’s hands. To racers that new meant that additional support beyond what had already been provided had ended.

In an interview with Mac McKellar before his passing, he told me that word came down from above to drop all development and support and that anyone caught violating that policy would be terminated without question. That signaled the end of Pontiac’s Super Duty program. So what does its ingenious leaders do when racing so strongly influences sales? It takes what it learned from racing and tames it just enough to be driven on the street! And with that, the GTO was born.

This article from the February 2, 1963 printing of The Charlotte News best describes the severity at Pontiac and Chevrolet.

Conclusion

While Kennedy’s antitrust action against General Motors may have played a role in the corporation’s decision to withdraw from racing, we see that a host of other factors likely contributed to it. GM was already under the federal government’s eye for its high sales volume so any additional scrutiny because of its involvement in racing not to mention the vocal outcries of GM’s competitors about it were unneeded and unwanted. It seems GM decided that fully enforcing its written policy against racing from 1957 was the best method of averting additional meddling.

Do you have any recollections of GM’s racing ban or perhaps any additional documentation you could share? I’d love to see it!